It’s a crime that fairytales have fallen to the wayside. People have been robbed of many life lessons they should’ve learned growing up, and, make no mistake, this was done on purpose.

Fairytales are crucial to any culture, and to proper childhood development. Not only do they contain moral lessons about right and wrong, courage, compassion, and the virtues, but they reinforce and preserve culture itself.

The last two books I’ve written happen to be fairytales. Now, granted, they are dark fairytales. Some might even go so far as to say “grimdark”. But I believe what I’m doing is important to evolve the genre and market it toward the audience it needs today. I’ll explain in a bit.

The Current State of Fairytales

What we’re seeing in the mainstream these days are subversions of fairytales.

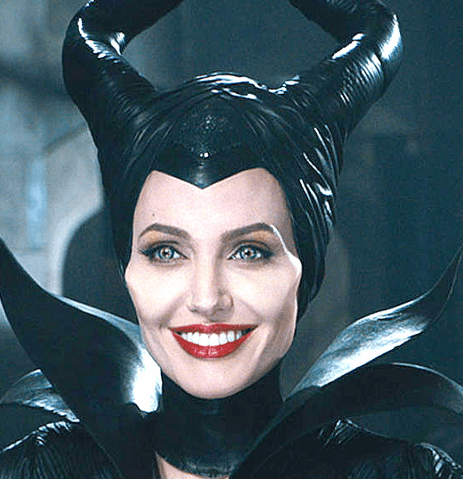

For example, famous fairytale villains are now “misunderstood”. Turns out they were never evil; maybe even the good guys all along. Evil characters like Shelob from Lord of the Rings and Maleficent from Sleeping Beauty have been given this treatment–portrayed as sympathetic, or even victims. And in some cases the story is retold with them as the main character.

But a fairytale must teach a moral lesson. And it typically uses fear to get its lesson across.

The fairytales of olde were aimed at children, so the story elements were understandably childish.

The moral: Don’t wander into the forest on your own. (Be obedient to your father and mother.)

The reinforcing fear: The forest is a scary place. (Some kids never come back.)

Cinderella teaches about perseverance and kindness. Hansel and Gretel cautions against trusting strangers. And so on.

But look around you: Today’s adults are the morally bankrupt ones. They seem to be the ones in need of emotional support animals, adult coloring books, and plastic nostalgia-bait toys just to get by.

Many aren’t even adults: By their own admission, they’re merely “adulting” (ie: pretending to be adults). And they are often more emotionally immature than their own children.

In fact, adults are setting such a bad example these days, they’re ironically becoming living fairytales, walking warnings to their own children about who–or what–they could become if they grow up without any morality or self-control.

So I suppose the audience I’m aiming for is twofold: Adults who have the moral grounding to appreciate these lessons, and adults who still need these moral lessons, but don’t realize it. In the case of the latter, I would hope my endings would tap into that lost childhood of theirs’ and disarm them with a decisive gut punch.

Chio Pino: A Reverse-retelling of Pinocchio might be broken down this way:

The moral: Child trafficking/grooming is a clear and present danger.

The reinforcing fear: Your child could be next.

I won’t share the moral of The Machine, but it should be one hell of an emotional gut punch for whoever manages to get through it.

The Wood Perilous

I believe it was L. Jagi Lamplighter who coined this phrase. She wrote a fantastic series of posts over the course of five years called In Defense of the Wood Perilous and it is well worth your time.

Traditionally, the woods were portrayed as a magical place in storytelling, wrought with peril. As I said earlier, this is crucial to fairytales because we need fear to be aware of threats as they come.

Without fear, we become complacent. And that’s the point of modern subversive fairytales: To portray the forest as a “safe space”, to leave us disarmed and unaware when a looming threat arises.

In her series, Lamplighter gives the example of a fairytale found within Neil Gaiman’s The Anansi Boys.

Anansi the Spider isn’t Gaiman’s creation. It’s a prominent character in West African folklore, though it originated in Ghana and has made its way over to Caribbean culture as well.

Anansi is always portrayed as a trickster, and as one who gathers knowledge and keeps it secret, hording it for himself. Using these secrets, he uses cunning to lie about his weaknesses and pretend they are virtues.

Sound familiar? Just like Anansi, our propaganda machine use these exact same techniques. So do alchemists.

The particular fairytale featured in The Anansi Boys tells of how Anansi the Spider is mortal enemies with Tiger, the hunter.

Tiger not only threatens Anansi, but the people of a nearby village. He is fierce, but only eats when he’s hungry because he’s a creature of nature.

When Tiger next comes to the village, Anansi is there waiting for him. He tells Tiger a tale so frightening, it causes Tiger to run away, tail between his legs.

When the people of the village see Tiger afraid and running, they laugh. They decide they no longer fear Tiger and consider Anansi the Spider their hero for scaring Tiger away.

Hauntingly, the story ends there, leaving the disturbing question: What happens when Tiger gets hungry enough to come back and try again?

Well, thanks to Anansi–and the magic of lies–the people are now complacent.

It turns out Anansi’s true goal wasn’t to defeat Tiger, but to disarm the people against him, because as much as Anansi hates Tiger, he hates the people more.

The Deeper Magic

There are two kinds of magic in the real world: The magic of truth, and the magic of lies. For that reason, fairytales are inherently magical.

The morals in traditional fairytales reinforce truth. And the magic inherent in truth is the magic of God Himself. The Deeper Magic, as I’ve blogged about in the past.

The morals in subverted fairytales, on the other hand, reinforce lies. They are designed to disarm us so threats can swoop in and have their way. This is the magic of alchemy, and, by extension, the magic of Lucifer. Bad guys are good guys. The wood perilous are not perilous at all. Tiger isn’t a threat. If you invite a snake into your home, it won’t bite you, it’ll become your best friend.

The more liars there are involved in a scheme, the stronger the magic becomes. One liar is a threat, but two liars are outright dangerous. A magician’s tricks become all the more convincing when he has a friend in the audience willing to lie about having ever known him. A miracle cure potion is a difficult sell, unless of course you have a liar willing to give testimony to the audience on how it changed his life.

C.S. Lewis’ The Last Battle portrays this concept perfectly. The main villain gets his dim-witted best friend to lie with him, and they’re able to fool almost everyone in Narnia with a scheme involving a fake Aslan. Because the main villain is reinforced by his friend, what starts as a simple lie leads to the Anti-Christ and even the end of the world.

There are few things more powerful than a coordinated lie, but in the end, the immutable truth always wins. This is so even in the final pages of The Last Battle.

But if we don’t want the world to burn before the truth has a chance to re-establish itself, fairytales need a major comeback, and it’s up to us to write them.

6 thoughts on “On Fairytales and Their Importance”