I believe we’re narrowing down the answer to the Riddle of Iron. Let’s see what else we can figure out for the glory of the #IronAge!

Part 1. (What is Sword & Sorcery?)

Part 2. (The Tower of the Elephant)

Part 3. (Jirel of Joiry)

Part 4. (The Historic Riddle of Steel)

Part 5. (The meaning behind the Riddle of Steel in the ‘Conan the Barbarian’ motion picture)

Part 6. (The Importance of “Appendix N”)

Part 7. (Definition for the #IronAge)

Part 8. (What NewPulp can teach us/Review for Tales From the Magician’s Skull #11)

Sword and Sorcery in Unexpected Places #1: The Maxx

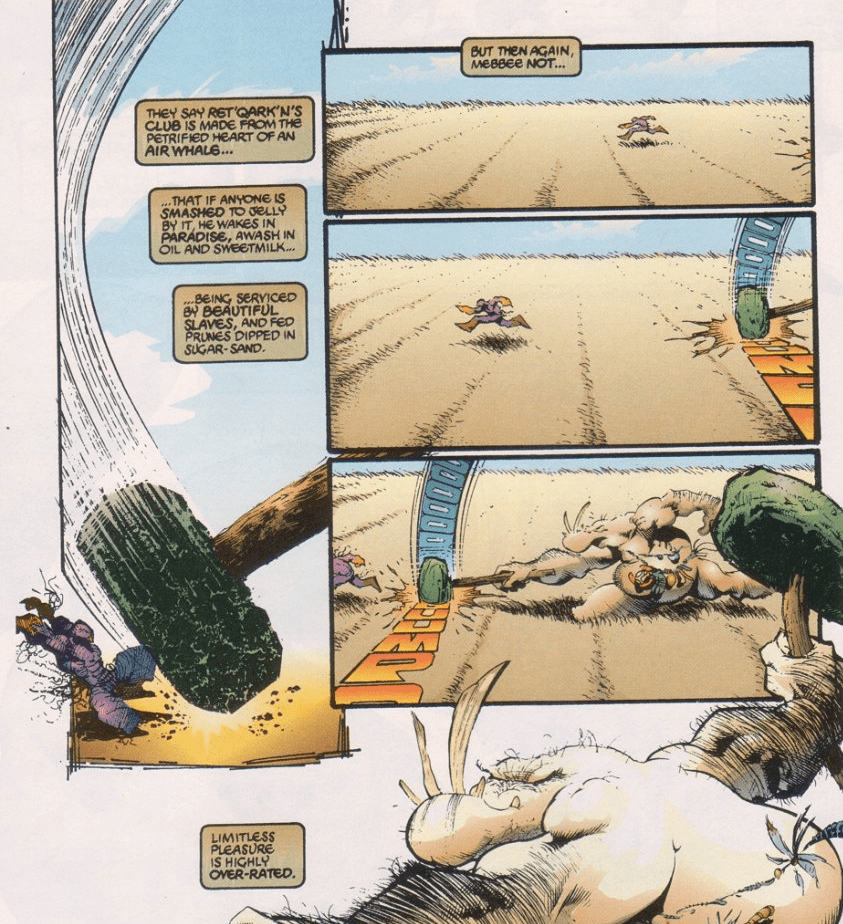

Sam Kieth’s “Outback” from The Maxx gives me definite Sword and Sorcery vibes.

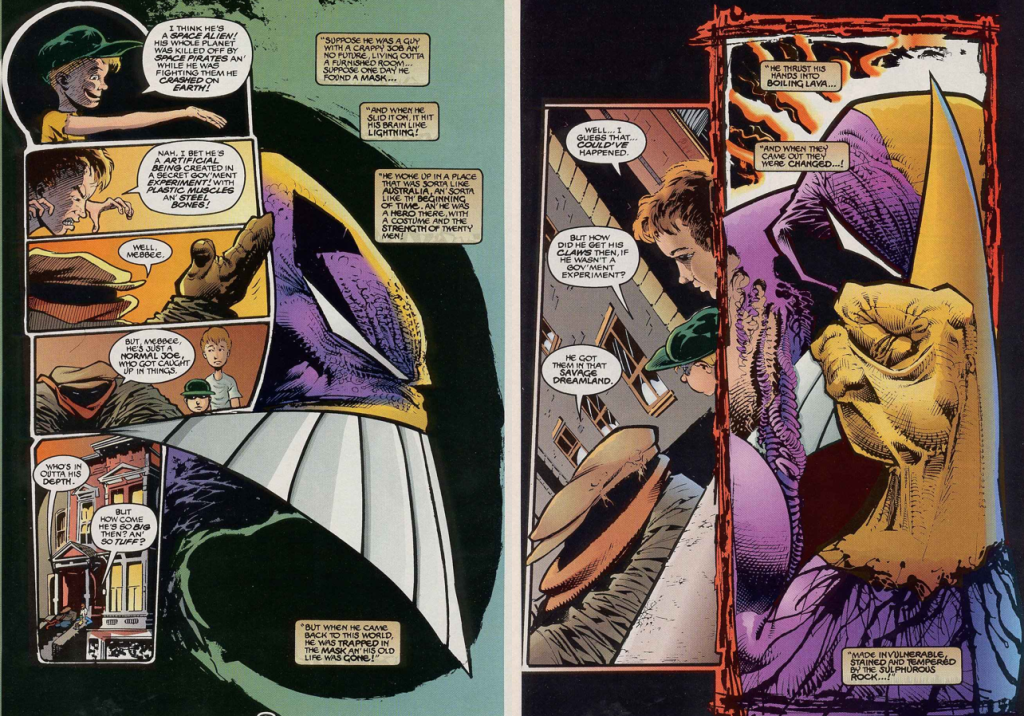

Maxx lives in two worlds at once: One is the modern world and the other is the “Outback”, brought about by his psychosis. Or perhaps it’s the other way around – Maybe the Outback is real. But for simplicity’s sake, let’s call it Real World vs. Outback.

(Note: I have read all 35 issues, but only mild spoilers up to issue #2 can be found here.)

In the pages of The Maxx, Kieth (and William Messner-Loebs) created a fantasy version of Australia, much like how many of the NewPulp offerings I’ve read have utilized and reimagined real world locales. In this case, it has a clear narrative purpose.

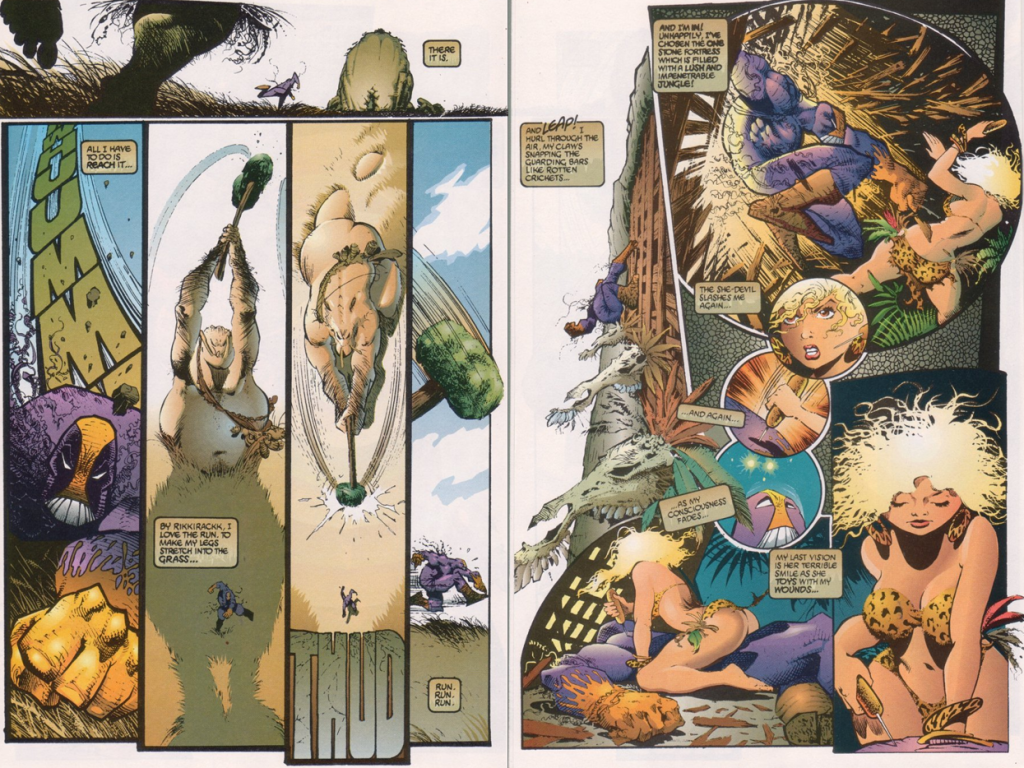

Maxx has a primitive mind in the Outback, but it’s instinctive, informed, honed for battle. He’s an expert on the threats that lurk there, from flora to fauna to traps. Reading these segments reminds me very much of the pulp era, with a little extra room for Sam Kieth’s unique brand of humor.

There’s even a bikini-clad buxom babe, the “Jungle Queen”. Her real-world analog is a naïve and hapless feminist freelance social worker named Julie Winters, out to “save the world” though she finds no joy in it, can’t see her own self-value, and can’t even save herself. She sees all her little flaws because she views herself through the harsh realities of a PostModern lens. She’s a student of Paglia, hoping feminism will provide modern-day answers to her modern-day problems. But that’s “PostModern heroism” in a nutshell.

Maxx sees beyond that – he sees a beauty in her that she can’t quite see.

No one’s brave enough to face threats head-on these days. Not like Maxx does. They’d rather just volunteer to help with the later consequences of evil, or keep a safe distance and donate from the comfort of their armchairs, trusting a corrupt system to do their civic duty for them.

Julie Winters is at least trying to help, but she’s doing it from a diluted mindset through a thankless system that pays garbage wages and fights against her efforts every step of the way. Perhaps that’s why she tolerates and even feels sympathy for Maxx. One wonders if she’d still feel that way in Current Year.

And so, Kieth artfully juxtaposes postmodern sensibilities with the pure freedom of stretching your legs, running past the wonders and sights of a magical pulp fiction prehistoria. For Maxx, this fantasy world is an escape from the pretentious postmodern world, a place free of mental illness, homelessness, misery, self-serving social justice crusades, and radical feminism. A place where a man can still be a traditional hero, protect his Jungle Queen, and be appreciated for it.

(Note that classic feminist Camille Paglia wasn’t/isn’t all that bad, by my estimation–But I don’t think she realized how slippery a slope we were all on at the time.)

I know Kieth was heavily influenced by Frank Frazetta, so I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn Kieth’s inspirations included some pulp-era fantasy as well. Mind, I can’t find anything definitive, but he did mark at least one of the drawings on his blog as 1940’s pulp-inspired.

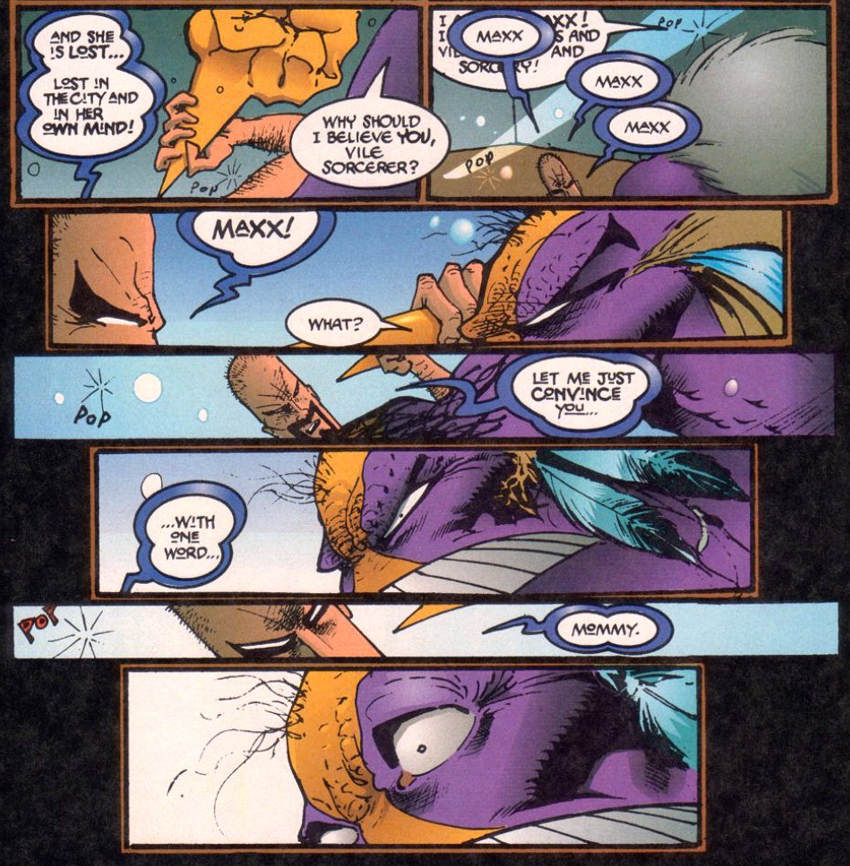

When primitive Maxx faces real-world Mr. Gone, it’s indeed sword vs. sorcery, Maxx’s molten rock claws being stand-ins for the sword-half of the equation (which are canonically his middle fingers, by the way). Gone is a sorcerer with answers Primitive Maxx couldn’t possibly comprehend. All he knows (or needs to know) is that Gone is evil, a threat to the Jungle Queen, and he knows he must vanquish that evil.

This is, of course, quite similar to how Conan fears magicians. Conan may not double deuce his enemies, but he gets the job done all the same.

Real world Maxx agrees with Primitive Maxx, because real world Maxx knows Gone is a rapist and serial murderer. Without spoiling too much, that promise of comeuppance is delivered early on, only for Gone’s story to drift into some serious and madcap Weird Fiction territory, dragging the main characters (and their unwilling psyches) along for the ride.

Conclusions

Remember back when young boys still thought traditional heroes were cool? Remember when they were encouraged to use their imagination?

Mr. Gone is special in that he’s a particularly cunning villain filled to the brim with secrets. His knowledge allows him to play the main characters like a fiddle and do it all from behind the scenes. He manages this puppeteering act by tactfully divulging his secrets, but also through clever use of his minions, the Isz. Masterminds like this are few and far between in Sword & Sorcery, but lend themselves well to creating a larger, overarching narrative between serialized installments.

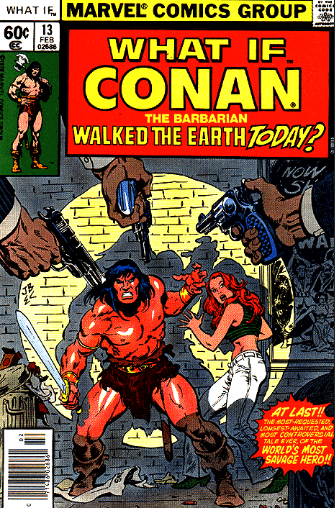

Is juxtaposing pulp-era Sword & Sorcery with today’s world (portal fantasy style) the answer? Is it the go-to way to reinvigorate the subgenre? Perhaps not. But it is a way. One that’s rarely explored.

Don’t know about you, but I want to live in a world where there’s still room for a traditional hero, a place where he can be loved and appreciated, despite his penchant for purple spandex.

Full disclosure: I grew up loving The Maxx, and even covered my bedroom walls, floor-to-ceiling, with Sam Kieth-inspired drawings and paintings I made during my teenage years. So I might be a tad biased.

4 thoughts on “The Riddle of Iron Part 9: Sword and Sorcery in Unexpected Places #1: The Maxx”