So far I’ve shared personal experiences, we’ve covered a little about Leigh Brackett’s celebrated career (which will be important later), and we’ve discussed the bizarre life and career of James Tiptree, Jr.

Today we’ll be hearing an industry professional’s take from author, editor, and feminist Kristine Kathryn Rusch.

If you’ve not heard of her, you probably should have–She’s a multiple Hugo, Endeavor, and World Fantasy Award winner, a sitting judge for the Writers of the Future contest, ran a publishing house that specialized in pulp reprints from 1988 to 1996, published dozens of novels/novellas/short stories, and has written for major IPs such as Star Wars, Star Trek, and X-Men.

In addition, she was the first female editor for the legendary Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction from 1991-1997.

You might recognize TMoF&SF from its heyday on the woodgrain magazine shelves in Barnes and Nobles (near the coffee shop before it was rebranded to serve Starbucks), but this ‘zine boasts a long and storied history of firsts stretching all the way back to 1949. It somehow managed to stay in print through 2019, outlasting many of its competitors; A feat which speaks volumes about its pedigree.

You may also recall this very same magazine is where Tiptree’s The Women Men Don’t See first got published.

Obviously, being the editor for this magazine is an honor they don’t just hand to anybody.

Rusch is well-positioned to comment on this hostile feminist takeover, as she watched the Hard Sci-Fi convention scene grow from a size where every fan worldwide (or as they were lovingly called back then, “the fen”) could fit in the confines of a single hotel, to the unwieldy behemoth it’s grown into today.

If you were lucky enough to attend conventions before nerd culture suddenly went mainstream, it was a smaller, far more intimate affair. There was a warmness to it. There were inside jokes. The fen (and other similar fandoms) were good, passionate folk.

And the fen knew that women were a huge part of the industry. They knew women had been professionally editing Sci-Fi since 1926. They knew not a year has gone by since 1968 that a woman hadn’t been nominated for a top writing award. And they knew Science Fiction’s most award-winning writer of all-time was also a woman: Connie Willis.

Keep in mind that these writing awards didn’t segregate into male and female categories like so many other awards do–These women were up against men as well.

At any rate, the fen knew. But newer fans? Not so much.

‘So, imagine my surprise when young writers who were trying to break into the field told me that women didn’t write science fiction.

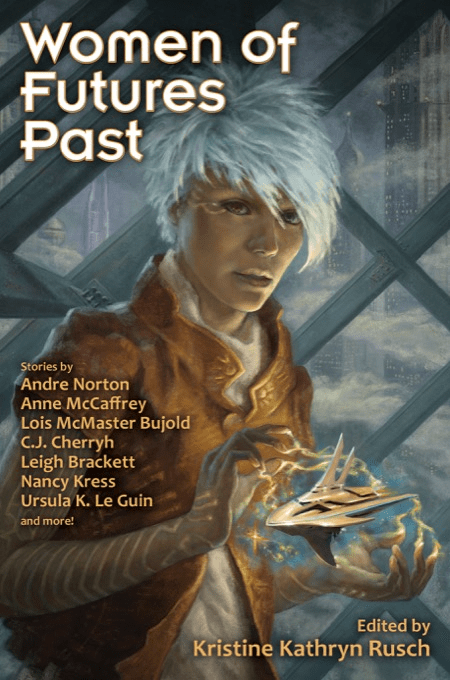

-Kristine Kathryn Rusch, From the Intro to Women of Futures Past, 2016

And then when the young writers saw the look of complete surprise on my face, some of them had the grace to realize who they were talking to—the woman with whom they had come to study how to write science fiction—and they would say, “Present company excepted, of course.”

Of course.

The first time I heard this, I wrote it off. The young writer who had mouthed this inanity wasn’t the brightest bulb in the chandelier. I figured she just didn’t know.

Then I heard it again, and again, and yet again. (Hell, I heard it just last week at my local professional writers’ lunch from a young woman who had been born in the 1990s…)’

Rusch grew frustrated at this new phenomenon and would list off exceptional SF writers in response. “What about Connie Willis?” she’d ask. Nancy Kress? Ursula K. Le Guin? Anne McCaffrey? Andre Norton? Lois McMaster Bujold?

Some of the aspiring authors would respond by saying they were all “exceptions to the rule”, but many would end up looking confused, saying they’ve never even heard of those writers.

‘Whenever I got the second response, I was stunned. Again, I figured ignorance on the part of the speaker—at first.

-Kristine Kathryn Rusch

But then I encountered that “who?” response more often than the “exceptions” response.

Something else was at play here.’

Rusch started a Science Fiction class for professional writers in 2013, and when prepping for the course, she discovered that she could no longer find most of the classic science fiction stories written by women — She was shocked to find that even the award-nominated and award-winning stories she was looking for were no longer being printed in any medium. They couldn’t be found in modern collections and anthologies.

“Best of” anthologies were skipping the female-written stories seemingly on purpose – Even the ones that had won reader awards in top genre magazines.

One might explain away these absences by claiming it was due to “unconscious bias”, or even blatant sexism, but it was happening far too consistently for it to not seem like a wider, more malicious organized effort was involved.

In 2014, Rusch looked up “women in science fiction” on Wikipedia. No listing. It suggested she try “women in speculative fiction” instead.

She followed the link to find an entry about how women were “denied entry into sf” (no citations given), and gave a paltry list of only six female sf writers, most of which had gotten published post-2000. No C.J. Cherryh. No Elizabeth Moon. No Anne McCaffrey.

Then Rusch started realizing she was being left off of female Sci-Fi writer lists, too. When she would inquire, she was told “repeatedly” she “didn’t write stories of interest to women”, as the main reason she was left off.

This didn’t bother her at first because she had been successful despite being left off of such lists. But in 2015, the straw that broke the camel’s back was when a new editor (Charles Coleman Finlay) was announced for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction.

Locus, the oldest and most well-renown fiction news magazine, reported on this and published a list of all of TMoF&SF‘s previous editors.

Rusch was the only one left off the list.

It went from Edward L. Ferman to Gordon Van Gelder–leapfrogging her seven year tenure, the time in which the magazine’s circulation was at its all-time highest. It was like she had been wiped from existence. Instead, it went from Ferman, to Gelder, to Finlay.

They had skipped the only female editor, the one who had run the magazine during most of the nineties.

In 1991, she’d gotten hundreds of letters of congratulations. Her landing that job was considered a triumph for females and feminists everywhere. She was called on the phone by many industry heavyweights, and even a recent Nobel Prize winner had wanted to personally congratulate her. But now? She was left off the list.

Rusch was furious and created a stink on social media. She demanded the issue be fixed. The editor-in-chief for Locus, Liza Groen Trombi, promptly fixed the issue, but claimed the list had come directly from corporate.

It seems doubtful Locus, given its pedigree, would somehow forget to include the first and only female editor by accident.

I was coming to realize that today’s young female writers had no idea that they weren’t storming the barricades—that there were no barricades and had never been any in sf.

-Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Following the Locus fiasco, Rusch asked other women she knew had been in the sf publishing industry for decades, only to hear similar stories and experiences of getting left off of lists and out of anthologies.

But that narrative in which there has been no female participation in sf, no women writing sf, in which women had to hide under pen names and initials because of being discriminated against . . . that narrative has triumphed over the truth.

-Kristine Kathryn Rusch

That narrative is insulting. It’s demeaning. And it’s wrong.

Fortunately, Rusch and her husband (sf author Dean Wesley Smith) are avid collectors of pulp fiction. They had archival proof that women had been part of the industry all along.

Thus, a project was born. A huge undertaking – Starting in 1926, when the first issue of Amazing Stories was published (and arguably the beginning of the pulp era explosion), the goal was to find all the female Sci-Fi authors to prove once and for all that the industry was not sexist.

They found that between 1926 and 1965, two-hundred and thirty-three different female authors were published in U.S. science fiction magazines alone, for a total of 1,055 stories. This list starts with Clare Winger Harris, who was the first woman to publish a story in a sf magazine: the June 1927 issue of Amazing Stories.

Out of the 233 women, her husband painstakingly created over 100 minibiographies for those he could trace any information for.

They also collected a list of twenty-six women who edited sf, fantasy, and weird magazines between 1928 and 1960. The list began with Miriam Bourne, the associate and managing editor for Amazing Stories starting in 1928. The list continues with both Madeline Heath and Marcia Nardi, both editors for All-Story in 1929. And so on.

The field didn’t just have women writers—it had really good women writers. These were wonderful stories, and I don’t believe they were overlooked at the time, because when I read them, they were all in Year’s Best collections.

-Connie Willis, 1992

Damon Knight also performed a similar study to Rusch and her husband, and came to nearly the same conclusions and totals. His search was even more exhaustive, uncovering further women who were writing under male pseudonyms.

Damon was married to Kate Wilhelm, one of the best sf writers in the field. In addition to her award-winning stories, she helped found the Clarion Writers Workshop, was one of the founders of the Science Fiction Writers of America group in 1965, and designed the actual physical template for the Nebula Award.

But look up information on Clarion or the Nebula Award today and you’d think Kate Wilhelm never existed.

Then there’s Judy-Lynn Del Rey, whose editing style was instrumental in ushering in the modern fantasy genre and helped launch some legendary careers. But look up Del Rey Books and you’ll typically only see Lester mentioned.

Betty Ballantine, of Ballantine Books, is a similar case.

C.L. Moore, whom I’ve covered here, is often dismissed as owing her career to her husband, Henry Kuttner, who allegedly helped write all her stories.

But that’s impossible–She met Kuttner precisely because he was a fan of her stories … and wrote her a fan letter.

It was around this time that Rusch began to fully understand what was meant by the commentary that she was left off of lists because she “didn’t write stories of interest to women”: She realized that women are often told what they should and should not write. They are often told that the only “important” stories are the ones about gender issues.

This was how “James Tiptree, Jr.” kept getting published–She was encouraged by the industry to do just that.

Even the heavily decorated Connie Willis fell into this trap, much to her chagrin. She was pressured to write Even the Queen about a world in which menstrual cycles were optional, and it (of course) won the Hugo for best short story in 1993.

…The episode that really convinced me I needed to write about this came when I was on a panel at a certain feminist science-fiction convention that shall remain nameless. (You know who you are.) I don’t remember what the panel was about, but I do remember that one of the panel members said that women only thought of their menstrual cycles as a “curse” because the male-dominated patriarchy had taught them to, and that left on their own, women would welcome and embrace their menses.

-Connie Willis, 2013

I thought then (and think now) that this was one of the most idiotic things I had ever heard. . . . After the panel, I did some research and found out that this theory was not just the ravings of one lunatic but actually pretty common in feminist circles, and then I talked to every young woman I could find (just in case attitudes had changed), and they were all as outraged and/or gobsmaked as I had been. . . .

Plus, some of my fellow women science-fiction writers had been on my case because I wrote stories about time-travelers … and the end of the world instead of writing stories about ‘women’s issues.’

So I decided to write one.

This is sad. Women should write what they want. Whatever speaks to them. For the industry to coach them, to groom them, to pigeon-hole them into only writing about social issues and gender… stilts genre innovation. It holds not only women, but the entire industry back.

Same thing happens to Black writers. They’re told they need to write about race issues, about oppression and injustice, about Afro-Futurism.

Try being black and writing a story about a Caucasian family living on Mars, battling robots, and the major publishers are probably going to ask for … changes.

These days, if you’re any shade of writer and have a story to tell that happens to only have heterosexual relationships, they’re probably going to tell you no. So really, it’s all writers. If you want to write in TradPub, you have to play their game.

Play TradPub games, win TradPub prizes.

Thus, awards like the James Tiptree, Jr. Award exist, to award “women and men who are bold enough to contemplate shifts and changes in gender roles, a fundamental aspect of any society.”

…a FuNDaMenTaL aSPEcT oF ANy sOciETY.

Whenever I look at modern anthologies that continue the “ongoing conversation,” they don’t have a very wide scope. In fact, they ignore much of what the most successful people in the genre write.

-Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Someone out there doesn’t want authors to write what’s in their hearts. They want them to write social commentary instead, using their identity as ammo. And whoever this someone is, they’re willing to go so far as to erase history itself, in order to gaslight entire generations.

They pretend women getting traditionally published is liberating … then erase them from history to pretend oppression is still happening. Then actively enforce which subjects women may and may not write about.

There’s nothing liberating about this.

Meanwhile, there’s an entire history–a veritable treasure trove–of excellent sf stories written by females about swords and planets and galactic suburbia. Stories that have been gatekept to be forgotten. And they don’t deserve to rot away in dusty bins.

But to extract these precious gems from history like an archeological dig and shine a light on them, I’m afraid, doesn’t support the narrative that sf is historically a male-dominated genre where females were never welcome.