Ah, the dawn of the nineties. Beginning of a brand new decade. Life was exciting back then, wasn’t it? No one quite knew what to expect. We seemed to get three mini-eras during that time:

- The “early” nineties (late 1989-1992, which had the most marketing misfires and most embarrassing styles. Kids were making the leap from 8-to-16-bit in gaming, and they could bring a true gaming experience on-the-go for the first time. Thanks to the effect of Tim Burton movies, Sonic the Hedgehog, and The Simpsons, most brands adopted an attitude and cranked it to 11. The Internet was a geeky curiosity and car phones were for the rich. During this short era, the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles had reached their apex and would never be cooler again.)

- The “high” nineties (1993-1995, which gave the decade the identity it was looking for, and brought grunge to the masses. Things were darker and edgier, but in a fine-tuned way that had pulled the reins back on the overdone attitude of the early 90s. It was an explosive era of creativity and growth across all mediums … even while MTV was rapidly turning away from music videos and toward “reality television”.)

- The “low” nineties (1996-1999, with the death of Kurt Cobain, grunge mostly died off. And the Super Nintendo went out with more of a whimper than a bang thanks in part to the Sony’s Playstation 1 stealing its thunder and the Nintendo 64 entering the arena (where most of Nintendo’s A-level talent had gone.) We started seeing more boy bands and other commercialized musical dreck thanks to Clear Channel monopolizing our airwaves, along with brighter-colored clothes and an overly optimistic, plasticky “feel good” movement that seemed to be an overcorrection to the high nineties, with the U.S. getting hurled into yet another identity crisis it never quite recovered from.)

Sandman got its start in 1989 right alongside Tim Burton’s Batman, and both had that darker, edgier feel that would later become the hallmark of the high nineties.

Marketers seemed to have a field day in the earliest of the nineties, throwing everything they could at the board to see what would stick, from parachute pants, to fanny packs, to “safe sex”.

And just in case you loved the eighties a bit too much and weren’t totally convinced it was a new era, all your favorite TV show characters were saying variations on the Suburban Commando and TMNT II lines: “It’s the nineties. I’ll sue him!”

But Gaiman had the high nineties figured out early, everything from the tone to the appropriate measure of political correctness (at first). You could feel that difference between Sandman and Black Orchid (which had debuted just a year earlier) and it was palpable.

Meet Hob

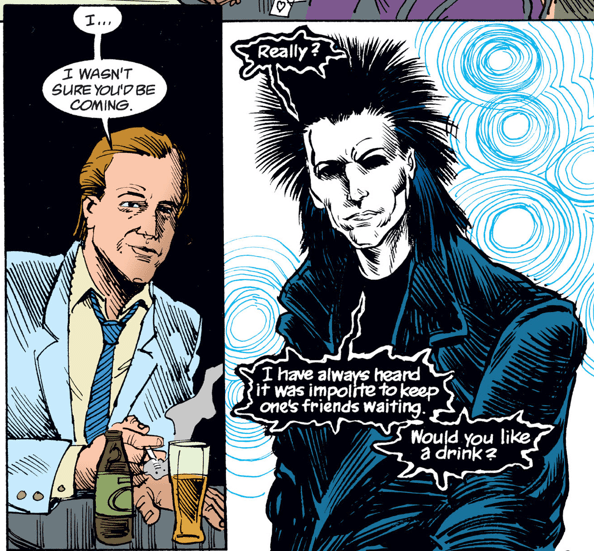

We first meet Hob in issue 12 of Sandman, January 1990.

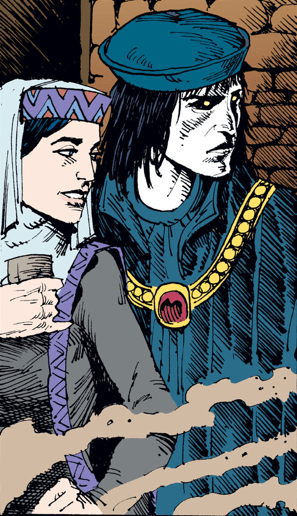

But the story proper is set 601 years earlier in the Year of Our Lord, 1389, where Dream and Death of the Endless are sharing an interesting discussion in the Tavern of the White Horse.

1389

Seems Death’s got her hands full with the Black Plague running amok, and she’s half-coSeems Death’s got her hands full with the Black Plague running amok, and she’s half-convinced the End of the World will be coming at any moment.

People in the background, meanwhile, are cracking jokes about the Papacy and dunking on the king.

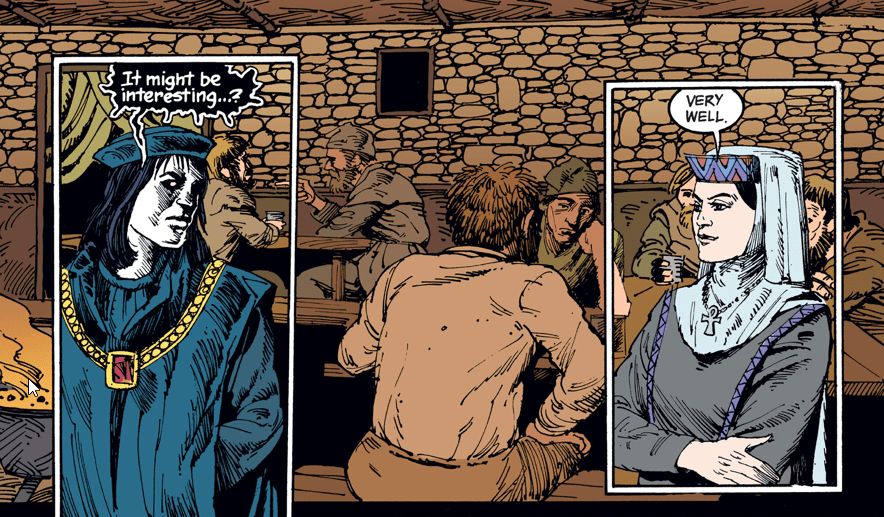

Enter Hob, drunk on penny ale, spouting off nonsense to his bar compatriots. Having seen half his village perish, and having battled as a soldier in the Caroline War, he decides that all he has to do to live forever is “not die”.

“The only reason people die, is because everyone does it. You all just go along with it. It’s rubbish, death. It’s stupid. I don’t want nothing to do with it.”

A preteen suffering from delusions of grandeur couldn’t have said it better. But perhaps even Death has seen enough quietus for one age and decides to give Hob exactly what he wants.

It’s up to Dream (a.k.a. Morpheus) to tell the poor sap what he’s in for, as he’s about to experience a life not unlike that of Frieren’s before she changed.

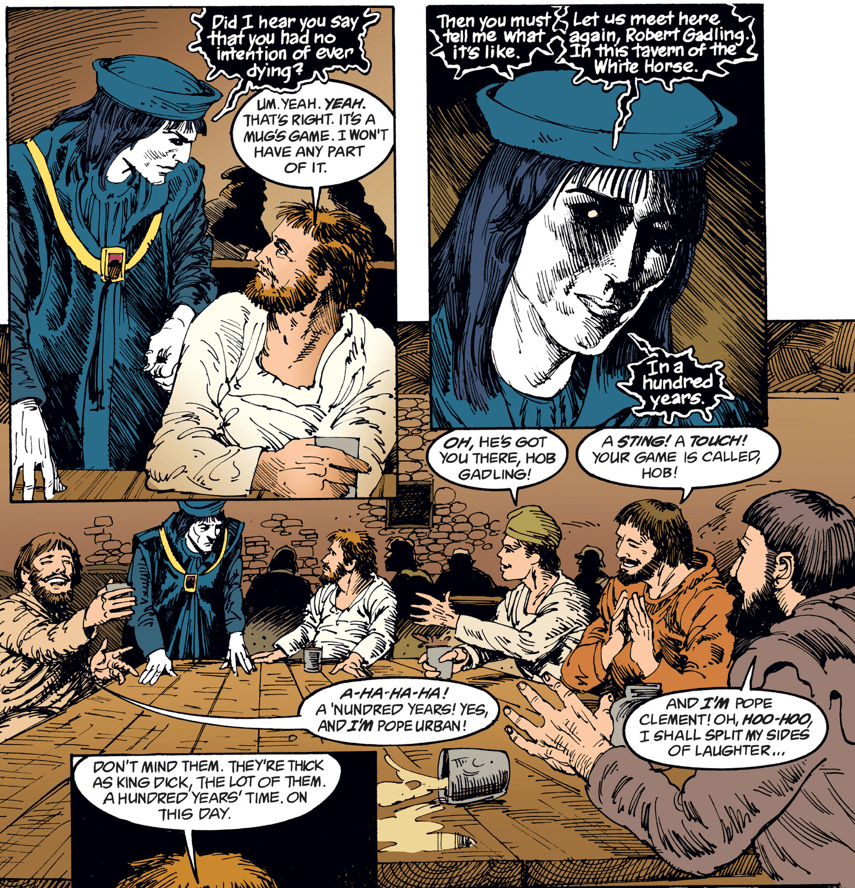

The drunken fool doesn’t even realize he’s already been blessed (cursed?) with immortality, and foolheartedly agrees to meet the stranger in this same tavern 100 years from now.

In the passing of just a few panels, everyone pictured above will be long dead. Except for Hob. Hob, and the stranger.

Just as it was for Frieren, everyone’s gone in a blink. But, as promised, Dream was waiting for him at the tavern, a full century later.

1489

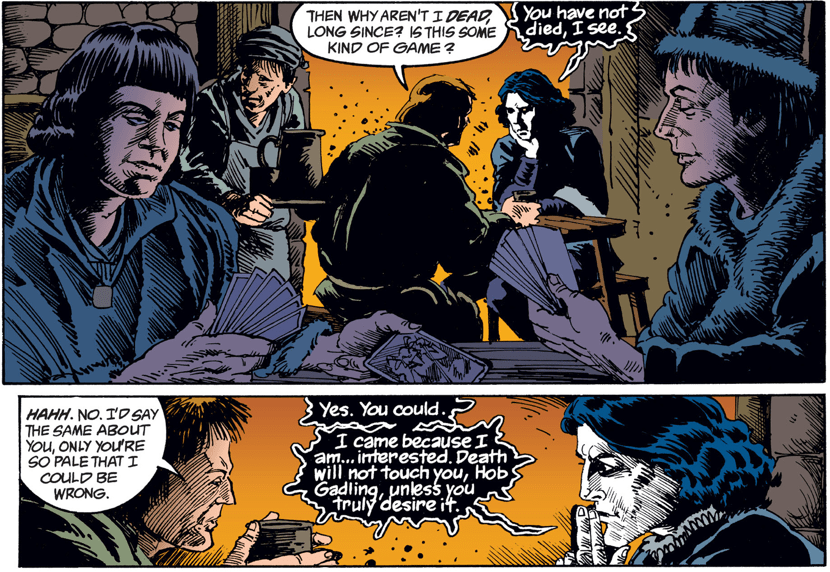

Right away, Gadling was concerned he had accidentally made some kind of deal with the Devil and felt relieved when Dream was able to convince him otherwise.

Not much has changed in 100 years. People are still worried about the latest diseases and drink away their worries in taverns.

But Hob’s different now. He no longer has a fear of death, so he no longer has a deadline to worry against. If he thought finding motivation to do much more than drink himself away in a tavern was difficult before memento mori, he’ll find it’s that much harder, now.

But he did get involved with the War of the Roses, fighting for both sides as a mercenary. Though he hasn’t done much with his extra time, he’d recently gotten into the printing trade with a friend, William Caxton, thanks to this new “printing press” invention.

“It won’t last,” says Hob. “But beats the Hell out of rotting to maggots in the ground, eh?”

“So you still want to live?” asked Dream.

“Oh yes.”

“A hundred years, then?”

“Oh yes.”

By the end of the conversation, Dream has Hob convinced that they’ve both not died simply because they’ve chosen to live forever. Hob also has no idea who Dream actually is, and still refers to him as the stranger.

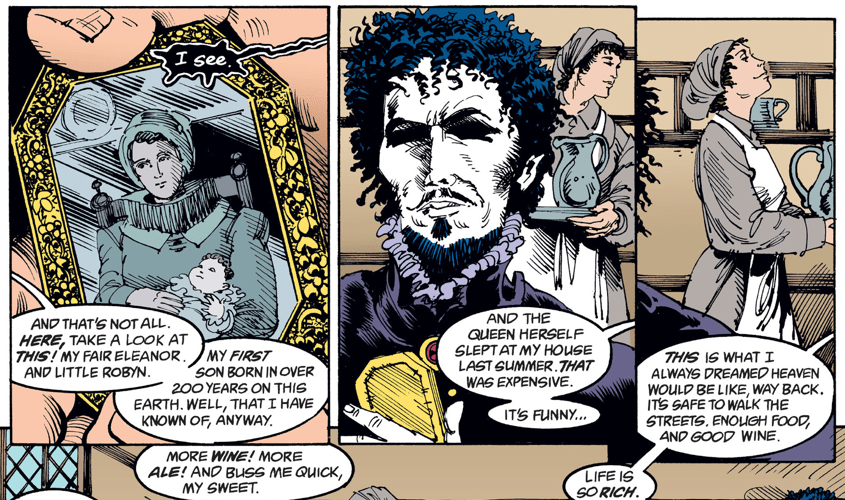

1589

It’s the late 16th century now, and Hob makes a show of his newfound success, almost as if he’s trying to impart that’s he’s become a “man of quality” to Dream. He goes by “Sir Robert Gadlen” now, rather than Hob (and is now posing as his own great grandson to avoid too many questions). But the reality is, he’s squandered some 240 years’ worth of time on this Earth.

Using the money he’d earned in the printing trade, he’d invested in the shipyards of Henry Tudor (Henry VII). And now he whiles away his days fulfilling his gluttonous and lustful cravings on the coin he earned.

But the only thing he really has to show for it is Robyn, his baby boy, even as he brags about having housed Queen Bess (Elizabeth I) for a night. He’s also married to a woman named Eleanor, and thinks quite highly of her.

Note also that he’s taken to jewelry and trinkets, to try to make the things that actually matter… last a little longer.

More time. More wine. More ale. More sex. That’s all life has to offer to those who want immortality on Earth. Always wanting more but never finding true satisfaction is not Heaven.

Even so, with his new wife and child, Hob seems to believe he’s found his own Heaven on Earth, his own eternity. He believes that all his troubles are now far behind him.

“Everything to live for,” he says, “and nowhere to go but up.”

Up? Interesting wording for someone who thinks he’s already in Heaven.

It’s a little cornball, but a young and struggling playwright (William Shakespeare) also happens to be within earshot at the tavern. A fellow puts a bug in his ear about making a Faustian deal to become a better writer, and Dream ends up leading the Bard away to have a private conversation. Frankly, Shakespeare’s a far more interesting and ambitious character than someone like Hob, so I don’t blame Dream at all for pardoning himself from the present conversation.

So far Death’s little experiment seems to be a failure. It’s clear Hob is surrounded by “Great Men” who invent, write, and create. But Hob himself is an opportunist, a man relying on luck to get by. A mercenary.

But at least Hob has created a family. Though his child is, in his own words, “the first one that he knows of in the past 200 years”, which suggests promiscuity.

He has exhibited pride (bragging), greed (flaunting his wealth), lust (sleeping with random women), gluttony (indulging on fanciful meals and expensive wines), and sloth (squandering his time as the movers of history rise and fall around him).

All that remains is wrath and envy.

At least Frieren spent her squandered time gathering spells, and Heiter may have been a bit of a lush like Hob, but he devoted his life to the cloth, got over his addictions, and raised a war orphan. They both built something that mattered, even before their respective redemption arcs.

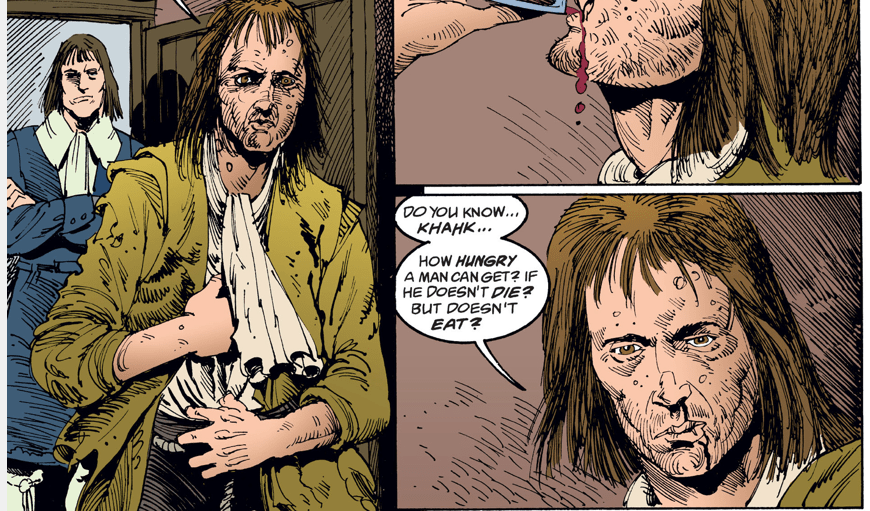

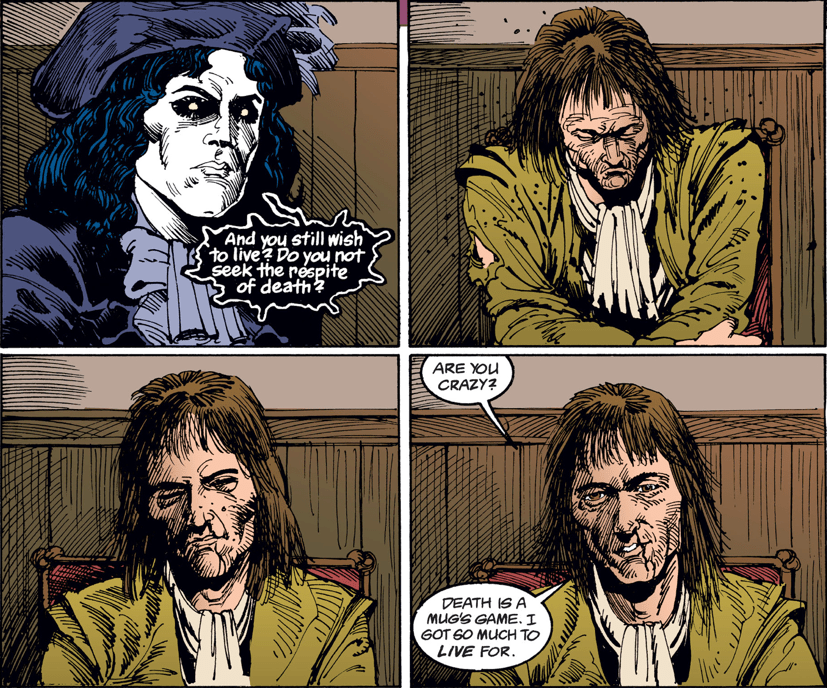

1689

Another hundred years. Hob is in such squalor that the bouncer won’t even let him into the tavern – until Dream intervenes.

Hob is penniless, possessionless. Eleanor died in childbirth and he doesn’t even remember what she looks like anymore (heavily reminiscent of the “Old Man Voll” plotline in Frieren).

And his son, Robyn, died in a bar brawl at twenty.

Seems Hob’s “heaven” wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

He spent too much time being miserable over it in the same town. After forty years of grief and complacency, the townsfolk started believing he was a witch who needed to be drowned.

“I’ve hated every second of the last eighty years. Every bloody second. You know that?”

1789

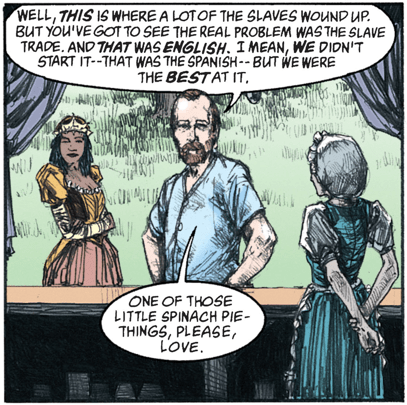

Here’s where the story takes an arguably unnecessary political twist: Hob’s made a mint trading cotton goods to Africa for slaves, packing them in boats “like sardines” to send them across the Atlantic in exchange for raw cotton, tobacco, and sugar.

“Wonderful system, really. Funny thing is, I sort of started it all. I mean, it was me that funded Jack Hawkins, what, two hundred years ago now…”

His only excuse for this behavior is,

“It’s a living.”

And that, unfortunately, is the reason for this entire subplot, as we’ll later find out.

But we’ll ignore that falsity for now, as there’s a real story still buried here. One grounded in truth. One about the price of immortality.

None-the-less, Dream says,

“It is a poor thing to enslave another. I would suggest you find yourself a different line of business.”

…which, of course, is a statement anyone can agree with.

But Dream, of all people, should know that slavery is as old as humanity. It is colorblind on the stage of world history and hardly started with Hob, nor will it end with the abolition of slavery in the New World.

During this meeting, supernatural hunter Lady Johanna Constantine shows up on rumors that every 100 years, “The Devil” and “The Wandering Jew” meet in this tavern.

This inclusion of the Wandering Jew legend is a way to weave a thread of antisemitism into this story, yet another hobby horse for writers like Gaiman. But The Wandering Jew is a quizzical bit of forgotten history – a 12th century rumor that a man who had taunted Jesus on the way to the Crucifixion was cursed to walk the Earth until the Second Coming.

Despite the Lady’s intrusion, Dream is able to whip up some magic and subdue her and her gang, setting the stage for another hundred years to pass.

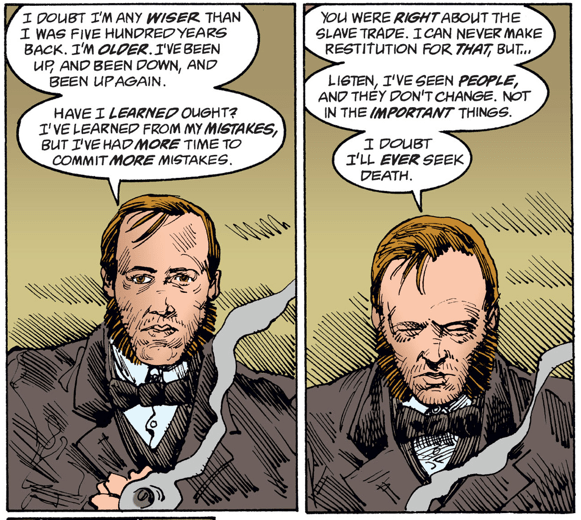

1889

Here we are in the nineteenth century, in the midst of Jack the Ripper and the smallpox epidemic.

Hob’s doing okay, but he’s realizing infinite time on Earth doesn’t necessarily help you get over your vices. What’s more, he’s feeling White Guilt, proselytizing that no amount of Reparations can ever make up for what he did to the slaves.

It’s interesting he would feel guilt at all, considering he has no reason to believe he will ever have to face divine judgment.

But Hob proclaims he knows why this stranger keeps meeting with him, century after century. It’s not to see how he’s doing, or even if he wants to continue living. Rather, he believes Dream is lonely and seeks friendship.

Dream is a prideful demigod and points the accusatory finger before storming out.

Perhaps this is Neil taking the moral highground over Hob, a strawman of his own creation. But it leaves a lingering question: Has Hob just chased out the only reliable constant in his ever-changing life?

1989

Fast-forward to the decade of VCRs and not much has changed. People are still convinced the End of the World is right around the corner. People are still boozing and smoking their fears away. People are still cracking inappropriate jokes about the Pope and Bishops, and instead of the king, folks are dunking on Margaret Thatcher.

There’s all the usual late 80s watchwords and fearmongering, ironically dispensed by the very same journalists who convinced them to hate the Pope and Thatcher in the first place.

But good old Dream shows up, looking like a goth version of an 80s stand-up comedian.

1990

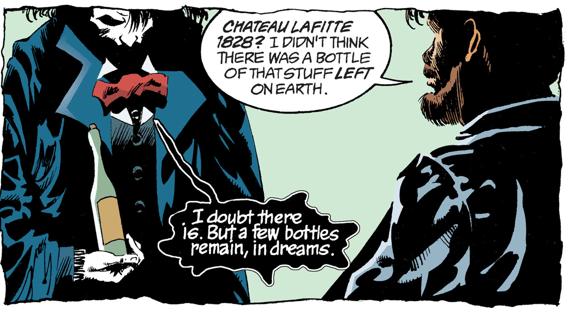

One year later (in Issue 22), Dream pays Hob a surprise visit in one of his dreams, offering a rare vintage wine that will carry over into the Waking World.

I’ve noticed in my time on this planet that the extremely wealthy find very few pleasures in life. Hang around millionaire doctors long enough and you’ll find they almost all have accolades, golf, and very precisely chilled wine cellars in common.

These are the creature comforts, the kinds of pleasures people try to enjoy in the here and now as much as possible, especially when they feel there may not be an afterlife waiting for them in the end. Dream understands this problem explicitly, being a wealthy immortal himself.

Not Too Terribly Long After…

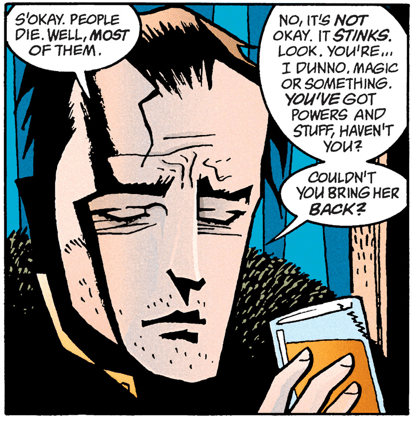

We jump to issue 59. And it seems Hob’s latest squeeze, Audrey, had crossed the road in front of a van and had tragically died. It was a hit and run.

Hob visits her grave.

I’m sure Frieren can agree with that sentiment.

Then Dream meets with Hob to offer condolences. He’s an emotional mess and asks for Dream to resurrect her.

Dream’s power doesn’t extend to life and death. All he can do is offer to ensure the van driver understands how much Audrey meant to him, and that she was a good person. Hob settles for that.

It’s interesting to note that most of his loves seem to die from tragic events. They never seem to reach old age. Almost like Hob carries a curse.

And Three-to-Four Years After That…

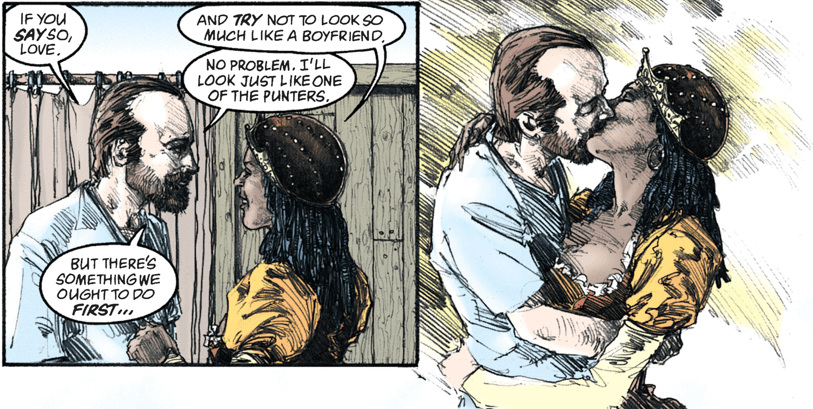

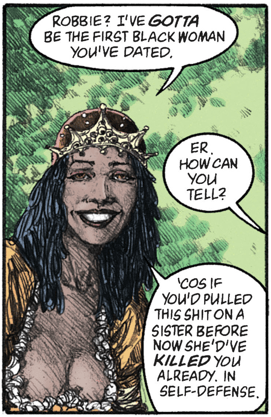

We catch up to Hob going to a renaissance fair with his latest squeeze, Gwen.

Perhaps someone should warn her of the curse. Wouldn’t be surprised if she catches a stray arrow to the head during a botched re-enactment. But Hob wanting to go to such a fair makes perfect sense for nostalgia’s sake (although we later find he doesn’t want to be here and this is Gwen’s idea).

Gwen is his American girlfriend, by the way. He’s flown to the U.S. out of guilt for his past … and met Gwen that way.

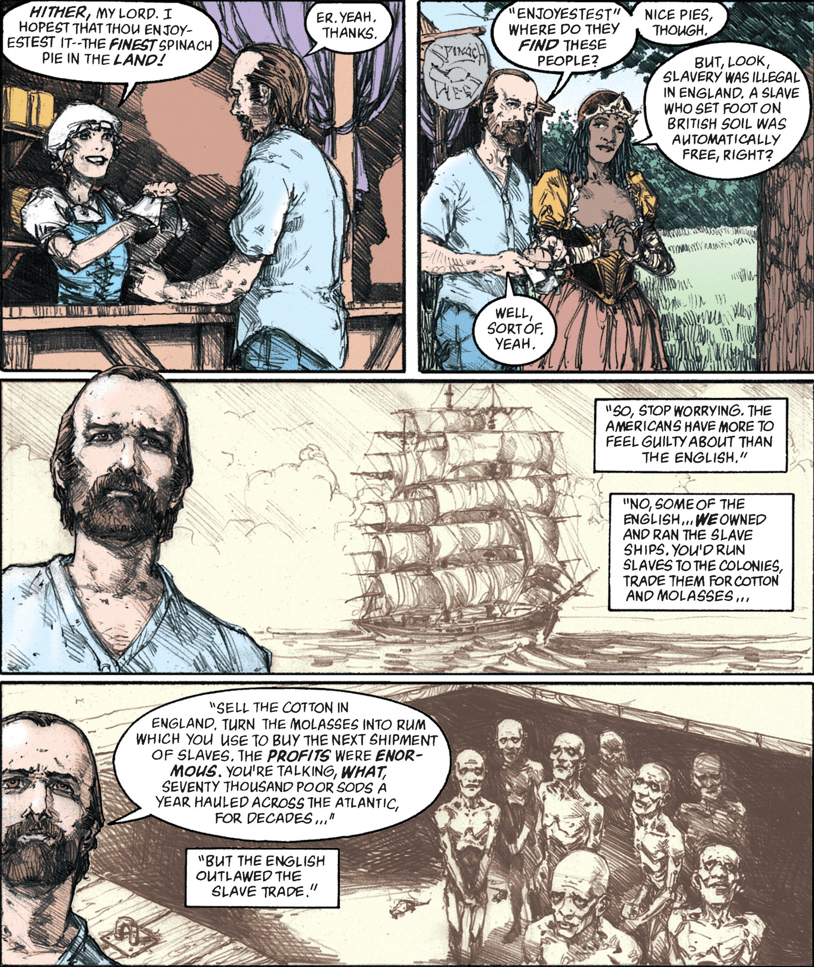

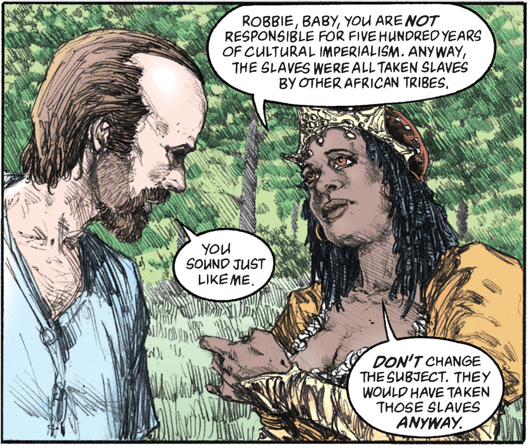

Hob then goes off on an uncalled-for white guilt tirade, trying to throw all of modern Europe under the bus (even though it was something he himself was directly involved in… and it was something all the folks around him weren’t even alive for).

A lesson Hob and Gaiman need to realize is that history is there to learn from. But no amount of Reparations will ever make something “okay”. Sometimes, all you can do is vow to live by the virtues and move on.

But the flogging continues.

Page after page.

Panel after panel.

If you felt guilt while reading this, it would be like being whipped over and over again without repose, without allowing the lasting sting even a moment to cool.

Robbie (Hob) is projecting his own sins onto the kind fairgoers around him. I think we can now safely add the sin of wrath. And, make no mistake, he’s dating Gwen out of guilt.

Self-flagellations over a dredged-up distant past does no one any favors. It just keeps the subject topical by resurfacing it over. And over. And over again. But Gaiman knew if you repeat a lie often enough, it becomes the truth. Magus tactic 101.

And in this case, the lie is in how he’s dispensing blame while pretending that slavery before and outside of the Trans-Atlantic trade did not exist. He’s just throwing his few cents toward paying the Devil his due along with the rest of the industry.

Or perhaps. Perhaps, Gaiman felt a deep-seated guilt about enjoying the art of slavery himself? (Again, allegations.)

But at least Hob’s having fun, right? Well, as it turns out, not so much…

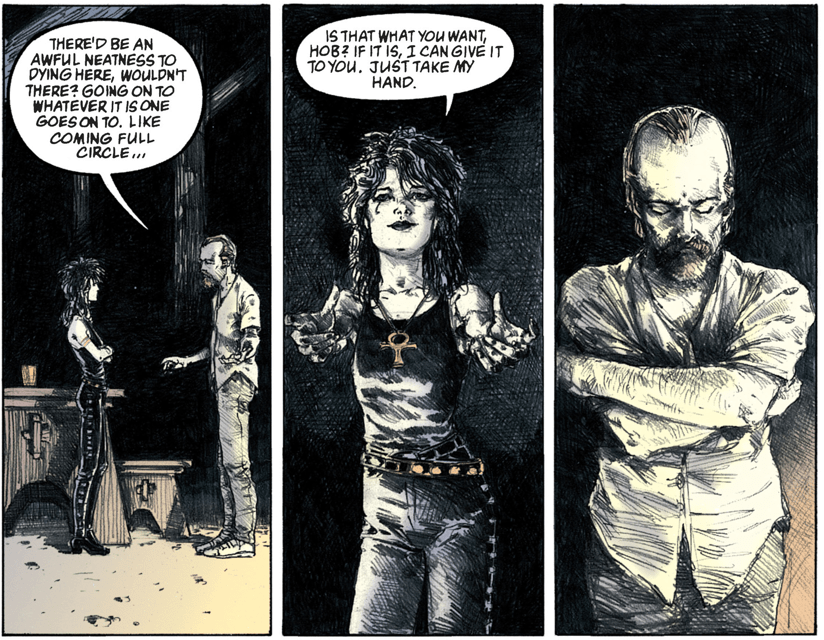

Death sits down next to him for a chat. And ol’ Hob reveals he hates how fake the ‘murricans are making this festival, with their “piss beer” and bad accents.

“I feel like Billy the Kid would have felt at a South London Wild West show. It’s like chewing on silver foil. ‘Orrible. I dunno what Gwen sees in it.”

Cultural appropriation at its worst, people! How dare Americans have a good time and try to celebrate European culture?

For those who have never experienced a Sandman story until now, my apologies. They’re normally better than this. But this story illustrates quite well how not writing in service to the story–and failing to focus on the immutable truths of our world–can muddy any tale and make it age like milk.

At least Death’s got our back:

So Death is here to ask if he’s ready to go. And he provides an interesting answer:

Hob says dying is more of a “slow” thing for him, like a thief taking little things from you here and there, until…

“…one day you walk ‘round your house and there’s nothing there to keep you, nothing to make you want to stay. And then you lie down and shut up forever. Lots of little deaths until the last big one.”

Death says it’s a theory she’s heard before.

Hob presses her, wanting to know what will happen if he agrees to die and she plays coy, asking him what he believes.

He smugly recites some pretentious Rudyard Kipling poem about reincarnation at first. But he’s doesn’t sound so sure:

“Is that the truth of it? Do we come back again?”

She smirks. “You’ll find out, Hob.”

Reincarnation is a nice, easy answer for him. If he’s right, it’ll mean he won’t have to pay for his sins in any meaningful way. But it’ll also mean there’s no system for cosmic justice.

By refusing to die, he’ll never know the truth. And no amount of meditating or studying poetry will get him there. The only way to know is to pull back the curtain by letting go of his immortality. The curiosity eats at him, day after day, century after century. But he’s afraid of taking the leap.

I think we can add the final deadly sin, envy, to the list. Envy for those who know what happens after they die. Envy for those who do not fear their death and final judgment.

The real Hell of his existence is that, deep down, he knows. Remember, he was concerned in his first meeting with Dream in 1489, believing he must’ve accidentally made a pact with the Devil. He was also concerned that Dream may have made some sort of Faustian bargain with Shakespeare. Even Johanna Constantine thought Hob had been meeting with the Devil each century, so it’s a clear-running theme throughout.

Well, if the Devil exists, then so does God. And so does final judgment.

Hob’s a coward. A coward full of guilt. He’s not ready to die because he’s not ready to face St. Peter. But maybe… maybe just a few more centuries of self-flagellation and he’ll be ready. Maybe just a little more pain and loss and virtue-signaling will get him there.

Maybe that’s the lesson right there: That no amount of Reparations can fix something, even if you have infinite time to feel guilt.

All these centuries later… and he’s not learned a dang thing. He hasn’t learned how to be truly moral. Or how to seek forgiveness. Or how to believe in anything… even while supernaturals are staring him right in the face. He’s just like Rudeus Greyrat, having been given a miracle on a platter, only to squander it.

The excuse he gives Death is the eyeroll-inducing punchline to this whole tale:

“Anyway, Gwen’d kill me.”

And that’s the last we see of ol’ Hob in Sandman. He’s still out there, somewhere, I’m sure. Probably with yet another girlfriend. Probably still wondering about the mysteries of the afterlife, still punishing himself daily while deflecting slaveblame toward the United States via BlueSky.

One thought on “Sandman: The Tale of Hob Gadling”