It’s the age-old question: Where do writers get their ideas?

This presents a nice opportunity to continue our exploration of Sandman tales, which I still cherish very much despite the recent allegations.

(And if you stay tuned, I think I might have a pretty good answer to this age-old question myself.)

We first meet Calliope in issue 17. The story starts with a fictional famous writer–a “Richard Madoc”–who has seen some success in the writing world with his debut novel, but fears the expectations tied to writing a second book.

He’s in a clandestine meeting with a fan of his (a college anatomy professor), who managed to procure a bezoar made of human hair during a cadaveric dissection, claiming the woman he’d cut it from had a particularly bad case of Rapunzel Syndrome.

If you aren’t familiar with bezoars and their “magical properties”, perhaps you at least remember that bezoars were used as poison cures in the Harry Potter franchise, and that at one point, one saved Ron Weasley’s life.

Anything that cannot digest in the stomach, and instead collects there (more or less solidifying) qualifies as a bezoar. The word roughly translates to “antidote”, and they are often used as magical cures … or spell components.

Madoc is under serious pressure from his agent. Turns out he’s nine months overdue on his writing project and is dangerously in breach of contract. He keeps claiming he’s “almost finished” with his project, but in reality, he hasn’t even started.

This isn’t just writer’s block – Madoc is a man fresh out of ideas. Except for one: Employ a magus.

The magus and world famous author Erasmus Fry gleefully recounts the history of bezoars and their magical powers to Madoc, even namedropping “spy and magician” John Dee for having gifted a set to Queen Elizabeth I, only for Madoc to reach a boiling point.

The writer laments he can’t think of a single thing of worth to say, a single character people can believe in, or a single story idea that hasn’t been told “a thousand times before”.

The magus dryly replies, “Of course I know what it’s like.”

Gaiman was a little heavy-handed with the “thousand times before” part, trying to make Madoc seem like a tragically hipster “artiste”. Truth is, there are many things that can cause writer’s block.

But the end result is the same: Madoc can’t see beyond the empty page.

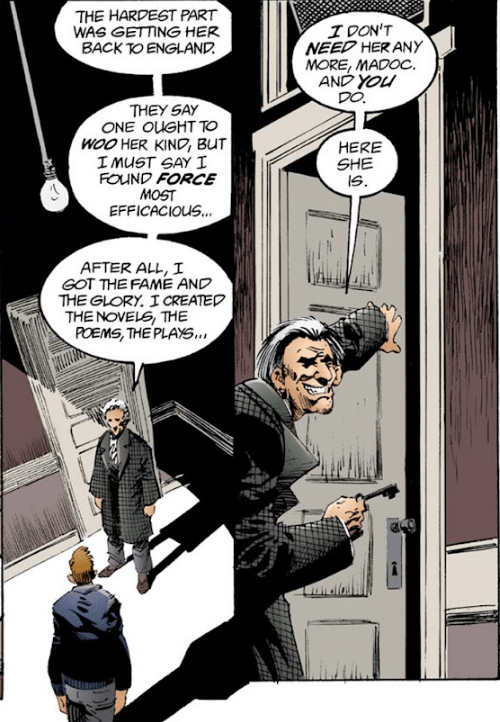

As mentioned, Erasmus has found fame in the writing world, having caught a muse some sixty years prior. Using his magus knowledge, he found her on Mt. Helicon in Greece, 1927, and ritualistically bound her.

Erasmus keeps her naked and in bondage, beats her and pleasures himself while also reaping the benefits of the inspiration she lends.

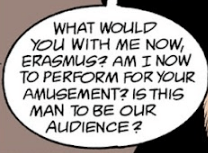

So Calliope says:

Calliope is a victim, you see. A victim of The Patriarchy.

At any rate, we learn that Calliope is the youngest of the nine muses, and was even Homer’s personal muse. Now she’s getting passed onto Richard Madoc.

Calliope, being a multi-generational slave, wishes deeply for her freedom.

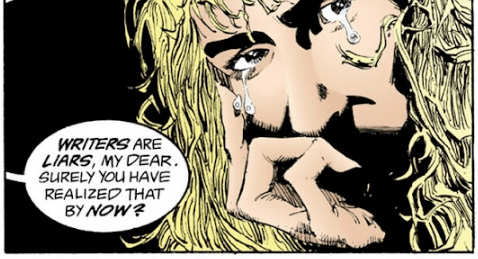

And then Gaiman goes for the worst magus lie of all:

You see, writers whose stories are not rooted deeply in Truth want you to believe that all fiction is nothing but lies. Writers who claim this are like Anansi the Spider, wanting to hide the Wood Perilous from readers’ eyes.

But there are always truths that resonate in storytelling, even within the most cynical, atheistic fiction you can find. For example, real rainbows have seven colors, writing in service to Current Year is a bad idea, and evil, selfish deeds always involve demons behind the scenes. These are all mechanisms of the Natural Law.

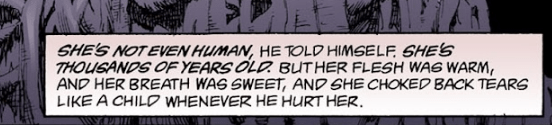

Because Madoc is a man, and a male feminist is writing this story, the desperate lead character does exactly what you’d expect: He locks Calliope in the topmost room of his home and wastes no time forcing himself upon her.

This is a dark glimpse into a deeply disturbed human being. (A-hem.)

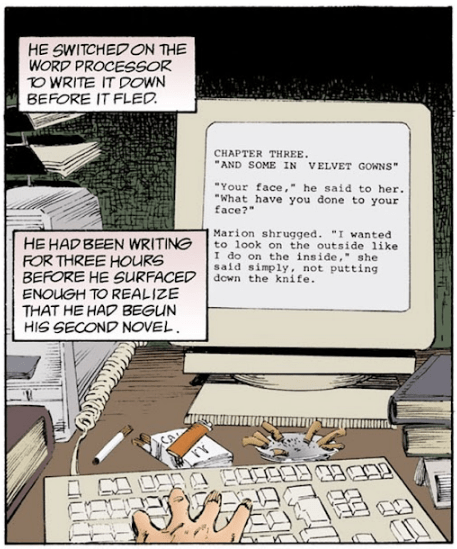

And then, just when Madoc was about to feel some small pang of guilt,

“Something shifted inside his head.”

And before he knew it, he was three chapters deep into his second novel.

Calliope, at her wit’s end, calls upon her fellow muses, begging them to set her free. But they cannot interfere since Calliope was “lawfully bound” upon Mount Helicon those many years ago. (read: an analogy for abusive arranged marriages.)

The muses remind her she was once with the Dream King, the “Sandman” himself, and that she had bore him a child. They implied he is her only hope for freedom, but that his coming is unlikely, since he is imprisoned.

Madoc, meanwhile, treats Calliope exactly like her previous master did despite her many pleas for freedom.

When he’s not abusing her, he’s hamming it up at book signings, demanding to be the director of his own screenplays, and bragging about how much better his work is compared to his contemporaries. He’s even cracking bad jokes at circle-jerk award ceremonies.

It turns out Dream had indeed been imprisoned. Just like what had happened to Calliope, he’d been ritualistically captured by a magus. And it took him 72 years to escape. (The story of his capture and eventual escape is told in The Sandman issue 1.)

After a television interview on the BBC, Madoc comes home to find an intruder: the Sandman himself.

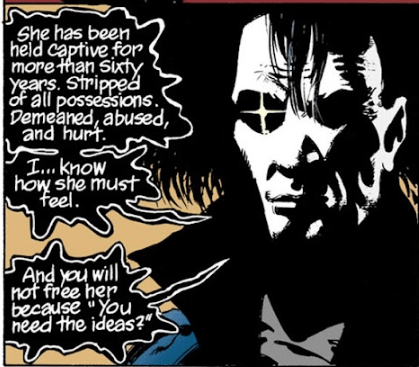

Dream politely, if sharply, asks Madoc to set Calliope free, and of course Madoc denies any knowledge at first, which displeases Dream even more.

Begrudgingly, Madoc admits he has her but begs to keep her. If just for a bit longer.

You see, this is how it always is with abusers: They admit to nothing, and then, when finally at the very end of their rope, they are sorry … that they got caught. (For some reason, I feel compelled to link to Gaiman’s apology essay “Breaking the Silence”, but I’ll refrain.)

This is the perfect springboard, Gaiman’s chance to stand on his pedestal and thoroughly whip this strawman with several doses of greater-than-thou morality.

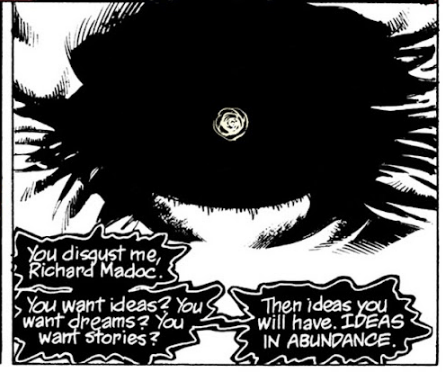

And then the twist:

Next morning, Madoc awakes with ideas. Soo many ideas.

He’s later found crazed out in an alley by the very fan who gave him the bezoar in the first place, his ideas scrawled on the filthy walls in his own blood.

There’s some denouement to this tale, but that’s basically it.

Disturbing as it was, there’s a bit of tongue-in-cheek humor to it – When asked which question writers get asked most, the answer is almost always,

“Where do you get your ideas from?”

It’s also hands-down the question authors like to answer least. If you’re ever at a writer’s convention, expect to get sarcastic answers such as, “From the Idea Fairy.”

But, well, now you know: We writers all have a muse locked away, somewhere within the confines of our own home.

…In other words, this story is Neil Gaiman’s extended sarcastic answer. He’s also told fans he gets his ideas from the “Idea-of-the-Month Club”.

He once wrote an essay on it, claiming that getting asked this question is one of writing profession’s greatest “pitfalls”, like how a doctor is often asked for “free medical advice”. I won’t link it, but you can find this screed on his official website. The essay’s called “Where Do You Get Your Ideas?” if you’re curious. But I’ll give you the gist of it right here.

After having grown sick of giving snarky replies, he finally started telling people,

“I make them up. Out of my head.”

The truth, he calls it. And it perplexes him as to why people are generally not satisfied with that answer.

He also disparages the popular idea that authors get their ideas from dreams.

“Dream logic isn’t story logic,”

he says. And I agree with that. But a great idea can come from anywhere, including a dream.

And then finally, when he was asked to speak in front of a group of first graders (I know, I know), he was again asked the age old question.

But this time, given the audience, he decided to divulge an answer a little less snarkily, with a little more aspiration and elbow grease applied, encouraging the kids to daydream and ask themselves simple questions such as, “What if?…” “If only…” and “I wonder…”

An example he gave was, “Wouldn’t it be interesting if the world used to be ruled by cats?” Which I believe, funnily enough, became the premise behind the very next issue of The Sandman.

Well, I have to hand it to Neil–He gave a pretty great answer, even if it was perhaps a little too John Lennon dreamer-ish.

But his answer’s not the whole story.

Unlike most grumpy authors living in their ivory towers, I don’t think it’s such a bad question to ask or answer at all. There are loved ones near and dear to me who struggle with creativity, and they find this subject in particular fascinating.

So I think I have an answer that’s more practical, and might even be miles better. Stick around for next time.